31 Jul 2024 Carbon pricing in the EU

Carbon pricing is a market-based instrument that aims to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in an economy. Two widely used forms of carbon pricing are carbon tax and a cap-and-trade system.

A carbon tax is a fee imposed on burning carbon-based fuels, such as coal, oil, and gas. Firms have to pay for CO2 emissions which encourages them to emit less. If set high enough, a carbon tax may prove to be a powerful monetary incentive for businesses to switch to renewable energy sources, such as wind, solar and hydropower.

In contrast, a Cap-and-Trade system, such as an Emissions Trading System (ETS), sets a limit on the amount of GHG emissions through a system of emission allowances. The allowances are assigned to companies either for free or through an auction process. Later, companies can trade allowances among each other. The GHG allowances system sets an upper limit on emissions in the economy. The possibility to trade allowances creates a market for emission permits encouraging companies to reduce their emissions and sell the permits to those who need them more.

There are two main differences between an ETS and a carbon tax. Firstly, the latter only puts a price on carbon, but it fails to limit the total amount of CO2 produced. In contrast, an ETS, by setting an emissions cap, imposes an upper bound to emissions. Secondly, under the cap-and-trade scheme, less polluting firms may sell their allowances to more carbon-intensive ones creating an emission permits market.

Most countries employ a combination of both carbon tax and cap-and-trade schemes. For instance, the UK has implemented its Emission Trading Scheme (UK ETS) – a cap-and-trade system launched in 2021 – and the carbon Pricing Floor (CPF), introduced in 2013 to ensure that the carbon price does not fall below a certain level.

On the other hand, the EU primarily implements a Cap-and-Trade system, known as the EU Emissions Trading System (EU ETS) launched in 2005 following the EU ETS Directive (https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32003L0087) adopted in 2003. The EU ETS is the world’s largest cap-and-trade greenhouse emissions market. Under this policy, the total volume of allowed GHG emissions is first set under the EU directives. Afterward, emission permits are auctioned and traded.

The EU ETS was developed in 4 phases:

- Phase 1 (2005-2007) covered CO2 emissions from power generators and energy-intensive industries (such as production of iron, aluminum, cement, and glass), and almost all allowances were given to businesses for free. Phase 1 established a price for carbon, free trade in emission allowances across the EU, and the infrastructure needed to monitor emissions. Phase 1 emission caps were based on estimates due to a lack of reliable data. The estimates turned out to be unreliable: in 2007 the total amount of allowances exceeded generated emissions and thus the price of allowances fell to zero (see graph below).

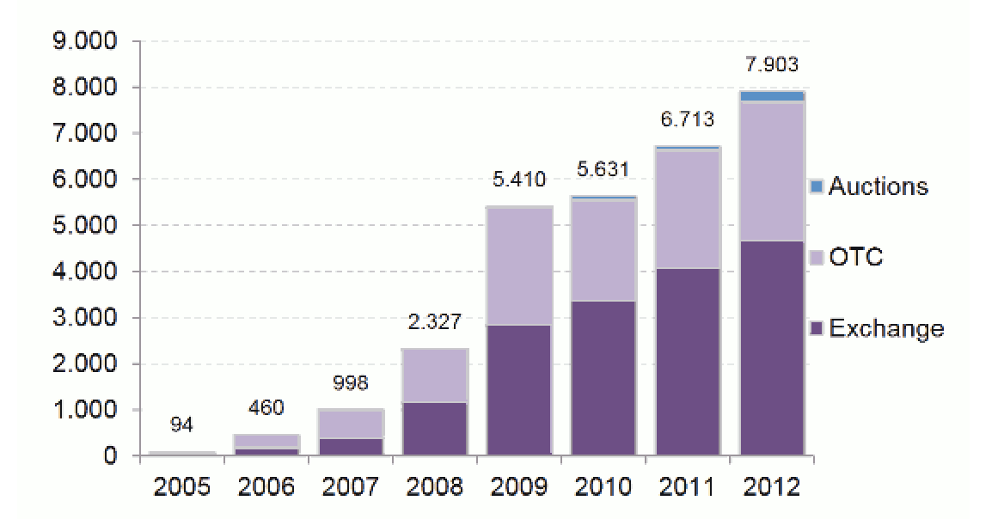

- In phase 2 (2008-2012) countries had specific emissions reduction targets to meet: cap allowances were on average 6.5% lower. The proportion of allowances allocated for free fell slightly to around 90% as countries started to hold auctions. Additionally, the aviation sector was also brought into the EU ETS. In phase 2, the cap on allowances was reduced thanks to data based on actual emissions; yet the 2008 economic crisis led to an excess of allowances and credits over emissions, significantly affecting the price of carbon during phase 2 (see graph below).

It is worth noting, that the cap on allowances was set on national levels through national allocation plans (NAPs), where the sum of the NAPs was the overall cap. The European Commission then assessed the plans to make sure they complied with the criteria set out in the Directive. Countries had to publish their NAPs by 31 March 2004 and by 30 June 2006 respectively for phase 1 (2005-2007) and for phase 2 (2008-2012).

- Phase 3 (2013-2020) changed the policy substantially: an EU-wide emission cap was introduced substituting the previous NAPs. Under this cap, stationary installations decreased each year by a linear reduction factor of 1.74%. Additionally, allowances were auctioned instead of being distributed freely and more gases and industries were included.

- In phase 4 (2021-2030), the UK is no more part of the EU ETS. As part of the EU ‘Fit-for-55 package’, a set of legislative proposals aimed to make the EU climate neutral by 2050, the EU ETS directive was revised to align it with the EU’s overall objective of reducing net emissions by at least 55% by 2030 compared to 1990 levels.

According to the ETS Directive (https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2023/959/oj), the cap on emissions will continue to decrease annually at an increased annual linear reduction factor of 2.2% (Art. 9 & 9a); it will further decrease at a factor of 4.3% from 2024 to 2027 and then 4.4% from 2028. Allowances comprising 57% of the cap are to be auctioned while the remaining 43% will be freely allocated (Art. 10). Free allowances are allocated according to efficiency benchmarks, rewarding the most efficient installations, generally, considering the risk of carbon leakage in each sector. The revised directive also includes emissions from maritime transport.

Following is a graph representing the evolution of carbon permit prices from June 2005 (the start of the EU ETS) to June 2024.

Source: https://tradingeconomics.com/commodity/carbon

The price of emissions allowances traded on the European Union’s ETS reached a record high of 100.34 euros per metric ton of CO₂ in February 2023. Average annual EUA prices have increased significantly since the 2018 reform of the EU-ETS. For what concerns the bottoms, as previously stated, in 2006 emissions allowances had been overallocated, causing an excess of demand and driving the emission allowances price to zero; in 2008, the global financial crisis caused a fall in aggregate demand leading to a decrease in carbon permits prices and in March 2022, the Russia-Ukraine war caused prices to crash to about 60 euros/tCO2 due to the expected ban on Russian energy imports.

The market in emission allowances has been very strong from the start and in less than 10 years the trading volume has increased by more than 83 times.

In detail, to date, the EU ETS covers greenhouse gases from specific activities, such as carbon dioxide (CO2) from electricity and heat generation, energy-intensive industry sectors (i.e. production of cement, glass, cardboard, pulp, paper, acids, bulk organic chemicals, iron, lime, aluminum, metals and ceramics), aviation and maritime transport. Additionally, the EU ETS covers nitrous oxide (N2O) from the production of nitric, adipic, and glyoxylic acids and glyoxal perfluorocarbons (PFCs) from the production of aluminum. Methane (CH4) will be included in the EU ETS from 2026.

The introduction of carbon pricing systems creates a risk of carbon leakage (or carbon dumping), especially since the price of carbon permits has been increasing. Carbon leakage refers to the practice when companies relocate their carbon-intensive production to countries with less stringent regulations. To address this risk the European Council and Parliament have introduced the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), a tariff on carbon-intensive goods imported from abroad. The EU CBAM will be operative from 2026. In its transitional phase (2023 – 2025) importers will be only required to report the emissions embedded in their products, without having to buy certificates. It will include the sectors of cement, iron & steel, aluminum, fertilizers, electricity, and hydrogen. From 2026 EU importers of goods covered by the CBAM will have to disclose the amount of carbon emissions embedded in their imports and buy the corresponding amount of CBAM certificates. In case the carbon tax has already been paid by the exporter, that amount may be deducted. In conclusion, the EU CBAM is an innovative approach to tackling the modern carbon leakage problem. Scientists and policymakers are starting to evaluate the efficiency of this measure.

For further information on carbon pricing and the EU ETS, please consult the following links:

- https://earth.org/cap-and-trade-vs-carbon-tax/#:~:text=While%20a%20carbon%20tax%20sets,the%20rise%20of%20global%20temperatures.

- https://www.edf.org/climate/how-cap-and-trade-works

- https://www.ft.com/content/49c25a8e-cc95-4656-a03e-0f47afced24e

- https://climate.ec.europa.eu/eu-action/eu-emissions-trading-system-eu-ets/emissions-cap-and-allowances_en#:~:text=In%20phase%204%20of%20the,linear%20reduction%20factor%20of%202.2%25.

- https://www.ft.com/content/1de4045e-bda5-4b24-b286-8b7c2b52afed

- https://www.sierraclub.org/sites/default/files/carbon-dumping-fee-climate-trade.pdf

- https://taxation-customs.ec.europa.eu/carbon-border-adjustment-mechanism_en

- https://climate.ec.europa.eu/eu-action/eu-emissions-trading-system-eu-ets/what-eu-ets_en#:~:text=The%20EU%20ETS%20works%20on,ensuring%20that%20emissions%20decrease%20overtime.

- https://climate.ec.europa.eu/eu-action/eu-emissions-trading-system-eu-ets/development-eu-ets-2005-2020_en

- https://climate.ec.europa.eu/eu-action/eu-emissions-trading-system-eu-ets/development-eu-ets-2005-2020/national-allocation-plans_en

- https://fsr.eui.eu/eu-emission-trading-system-eu-ets/

- https://climate.ec.europa.eu/eu-action/eu-emissions-trading-system-eu-ets/free-allocation_en

- https://www.statista.com/statistics/1322214/carbon-prices-european-union-emission-trading-scheme/